The sawn veneer

Between muscle power and waterwheel - the history of sawn veneer

When I look at an old piece of furniture, it's not just the shape or the proportions that make it so appealing - it's the wood itself. The furniture I work with is almost all veneered. And by that I don't mean what we understand by "veneer" today: thin sheets on MDF or chipboard, technically perfect but often soulless.

In historical furniture, the veneer is a sign of the highest quality craftsmanship. The base material is solid wood - usually oak or softwood - and the veneer has been selected with care and design standards. It creates tension in the surface, symmetry and a harmonious appearance.

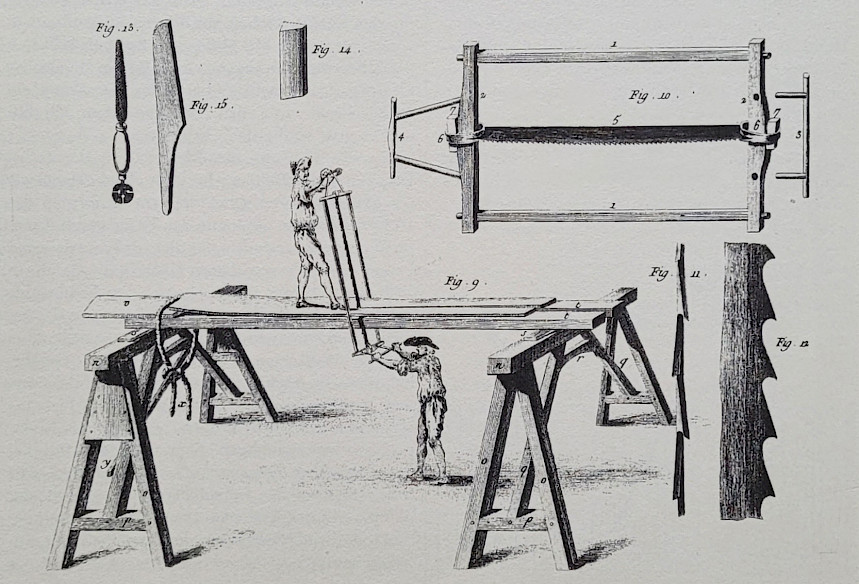

The Klobsäge - two men, one trunk, a lot of feeling

Until well into the 19th century, the production of veneer was purely manual labour - and a real effort. The central tool was the log saw, a large, frame-guided saw that was operated by two people. The log was debarked, levelled and clamped vertically. Thin layers were then sawn off in an even rhythm - so-called thicknesses, usually 2 to 3 mm thick. Ideal for further processing as veneer.

The cut had to be exactly parallel over the entire length - a job that required experience, concentration and a trained eye. When I imagine that thousands of sheets of veneer were created in this way - each one individually and by hand - then I realise again and again what a great achievement the craftsmen of that time accomplished.

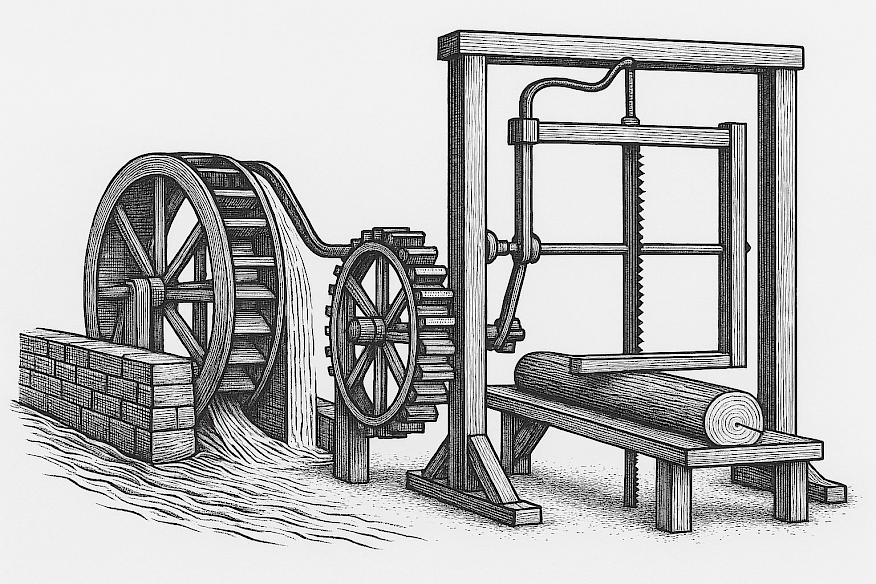

From muscle to mechanics - water power changes the craft

But the carpentry trade was also striving for progress. As a result, water power was utilised early on for wood processing, especially in regions with rich forests and good watercourses - for example in the Black Forest, the Alpine region or Scandinavia.

The vertical frame saw was developed in the 16th century and was established in many sawmills by the 18th century - albeit primarily for the production of beams and boards.

Only occasionally were these systems adapted for sawing thin veneer sheets - with finer blades and more careful feeding. But even then, finishing remained manual labour. For a long time, the block saw still dominated in many workshops because the purchase of finished veneer sheets was time-consuming and expensive and because you could choose the grain yourself when making your own.

It was not until the early 19th century - and then increasingly from the middle of the century - that the machine production of veneers became standard. Frame saws were technically refined, with more precise guides, finer blades and adjustable feeds. Initially they remained at a thickness of 2-3 mm - in the tradition of hand-sawn veneer sheets - but later they became thinner.

What makes sawn veneers unique

What particularly fascinates me about sawn veneers is their creative potential. Because the log was split into layers, neighbouring cut surfaces could be joined in mirror image. In English, this is known as bookmatched veneers - like the pages of an open book. The grain runs symmetrically to the central axis, creating tension, depth and rhythm.

What particularly fascinates me about sawn veneers is their creative potential. Because the log was split into layers, neighbouring cut surfaces could be joined in mirror image. In English, this is known as bookmatched veneers - like the pages of an open book. The grain runs symmetrically to the central axis, creating tension, depth and rhythm.

In the furniture I work with in the antiques trade, you can immediately recognise the signature of the original veneer production: the grain runs like a mirror image across two doors, across an entire furniture front or across the surface of a table top. It is a designed image, not a random woodcut.

And perhaps that is what touches me most about historical furniture: that it is not only beautiful, but also a testimony to true craftsmanship. And that this craftsmanship can be seen not only in the corner joints, the plane marks or the hand-forged fittings, but also in the unique beauty of the veneer.

Also interesting

Antique snooker table

The fine English way! I have fond memories of this great snooker table from around 1910. The well-known [...]Read more

Faux bamboo style furniture

Far Eastern exoticism in historicism Furniture with carving and turning work imitating bamboo is still [...]Read more